Serge Rompza, Node Berlin

Guest professor, leads a workshop about content creation

After graduating from Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam, Serge Rompza has co-founded the Berlin and Oslo based design studio NODE in 2003, together with Anders Hofgaard.

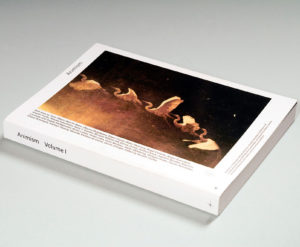

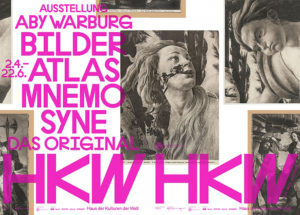

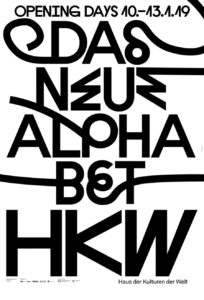

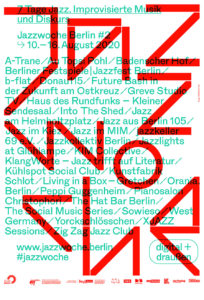

The two offices collaboratively focus on identity, print, exhibition and interactive work.

Clients include Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin, Vitra, MIT Program in Art, Culture and Technology (ACT), Lithuanian Pavilion / La Biennale di Venezia, Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA).

Since 2004, he has regularly been teaching at art and design academies across Europe.

“personal quote”